When I first trekked up to the beautiful blue pilgrimage lake of Gosainkund in Nepal in 1984, the national literacy rate was about 33% (less for women), and the average yearly income was about $160 per person, though much of the economy was based on a barter system. Infant mortality was very high, and health care was minimal.

Thirty years later, looking back at the transformation Nepal has undergone since founding the nonprofit READ Global, I am amazed and proud of the collective progress we have made. Literacy rates have doubled and per capita income has quadrupled.

In 1984 I had been conducting educational research in Philadelphia, and went off trekking in Nepal with friends. On this first visit four years before opening my own travel adventure company, Myths and Mountains, the country was an absolute monarchy, ruled by the late King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev. In a country about the size of Tennessee, the population was about 17 million.

Until the fall of the Rana dynasty in 1951, only the children of royalty were allowed to attend school, as keeping the populace ignorant was considered an excellent method of control.

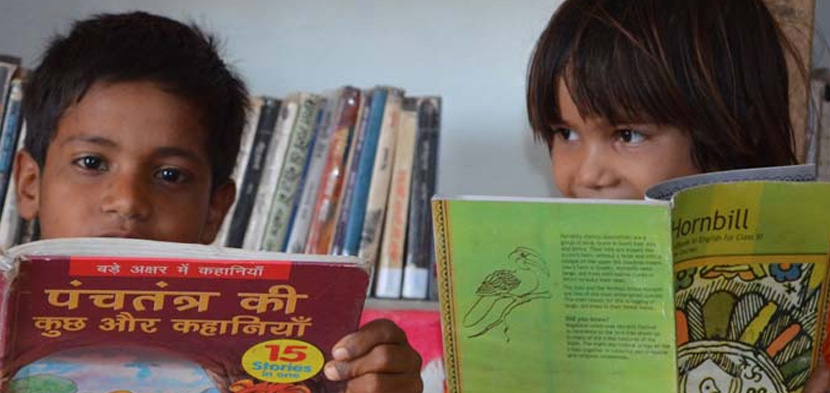

Thus, education by 1984 in Nepal was still in its infancy, with relatively few books in Nepali. Although most Nepalese speak Nepali or ethnic dialects, the only children’s books were from India in Hindi, and there was no culture of reading. To visit the house of a university professor and see no books whatsoever was common.

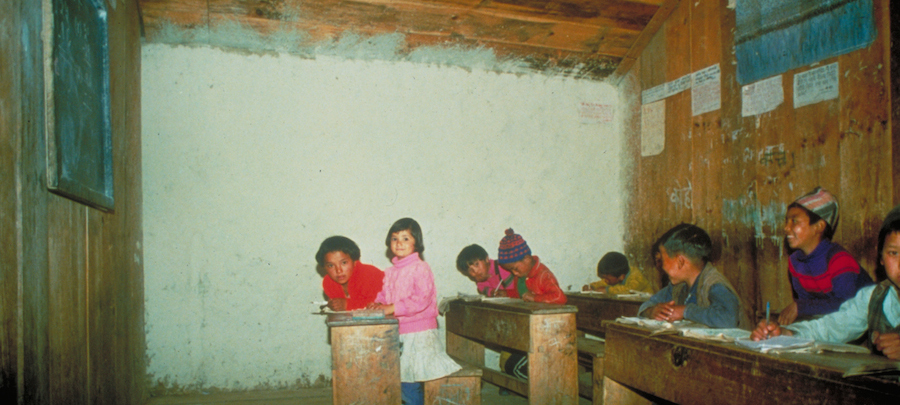

Schools, particularly in the countryside, often lacked roofs, much less benches or desks, and one classroom usually served multiple grades at a time.

Almost all learning was by rote, and most schools had an insufficient number of textbooks for their students, much less the materials for students to use when studying for their school leaving certificate (SLC) exams. Few students ever made it beyond elementary school; and even fewer, beyond secondary.

Teachers weren’t prepared either: usually, the average elementary school teacher had only finished secondary school and passed her SLC. Principals were not educators, but political appointees, usually from outside the district to which they were posted.

At an adult level, there were organizations conducting literacy training, particularly for women. But, since villages had few, if any, books, the retention rate for “neo-literates” was low, undermining the success of the effort. “Literacy” was defined as the ability to read at a third grade level.

In the early 80’s, there were “libraries” in Nepal, but the word was used very loosely. Lending libraries were almost non-existent, and books were so precious that they were kept under lock and key.

Most libraries were private, others were holes-in-the-wall begun by well-meaning aid workers with books in English. Books were moldy from the monsoon rains or eaten by silver fish, an insect in Nepal that loves to consume bookbindings and paper.

When democracy came to Nepal in 1991, a plethora of schools and universities sprang up across the country, with auxiliary campuses in different population areas. But the only real lending library in the country was the British Council Library in Kathmandu. Tribhuvan University and some of the “colleges” (schools for grades 11 & 12) had libraries; but many books were in English or Hindi and were outdated. Stacks were closed so students could not borrow the books.

Trekking through Nepal at this time for Myths and Mountains on some unusual and challenging itineraries, we wanted to give something back to the local people who helped us.

I was inspired by a simple wish from a Nepalese guide: to have a library for his village. So in 1991, the guide, six porters and I trekked on foot, carrying in 900 books in Nepali over a 10,000’ and 12,000’ pass to establish the first READ Center in Junbesi.

At that time, when I talked to people about using libraries as a catalyst for rural development, people laughed, aid workers scoffed at the concept, and no one cared about libraries, much less believed that they could be sustainable.

Fast forward 30 years. On August 31, 2014, the Panauti Community Library and Resource Center was inaugurated – the 50th READ Center to be established in Nepal.

Nepalis themselves had raised an unprecedented $88,000 from within their own country to construct this building – something unheard of. This is truly a testament to the love of libraries in the country, and their potential for community transformation.

Nearly 2,000 people packed the inauguration tent, spilling over outside for the opening – people from government, entertainment, and the international community, as well as locals. Today, children and adults line up outside of the library every day, eager to learn.

READ has now built 74 READ Centers across South Asia, having expanded to Bhutan and India to scale our work.

In Nepal, READ is one of the few organizations to survive the 13-year civil war unscathed, and is greatly respected in the country. Sanjana Shrestha, the Country Director, has appeared on local TV. Articles about the organization have appeared in local newspapers, such as ‘Kantipur’ and ‘Republica’, and READ representatives have been speakers in South Africa and Chile, as well as the United States.

The word “library” is on everyone’s lips and READ has inspired a variety of organizations that focus on libraries of different sorts – e-libraries, corners in local schools that have books for children to read, technical libraries and others.

All READ libraries have around 5,000 books each, a computer section and audio-visual resources, a training hall, and women’s and children’s sections. Each Center offers a variety of training programs in education, livelihood skills, women’s empowerment, and technology. All READ Centers also have a small sustaining enterprise that generates income to support ongoing operating costs. Panauti’s is a souvenir shop that is selling local handicrafts.

Sadly, Nepal is still one of the poorest nations in the world, but there is change.

The literacy rate is now above 65%, and the least literate are the older people who grew up under the late Rana and early years of the Shah dynasty without education. To be sure, quality is uneven throughout the country, but education is better, and parents desperately want to send their sons with clip-on ties and daughters with pigtails to school, so they have more opportunity than the parents had. There is now a market of readers, so writers are encouraged to write books in Nepali.

Libraries have proven their value as catalysts for rural development. If you build a school, it only serves the young. If you build a hospital, it serves the sick. But, if you build a library, it serves the entire community.

Yes, change has come to Nepal.

About the author:

Toni Neubauer, Founder, READ Global; CEO, Myths and Mountains

Dr. Antonia (Toni) Neubauer founded READ Global, as well as Myths and Mountains, a travel adventure company. She has been traveling to Nepal since 1983, and has visited 60 countries around the world. A former language teacher and education researcher, she has directed major studies on literacy and school-business partnerships in the US and served as a consultant to the Pew Foundation, Lilly Endowment and the U.S. Department of Education. She is a member of Wendy Perrin’s WOW List as the Trusted Travel Expert for Nepal and Bhutan, as well as Conde Nast Magazine’s Nepal Top Travel Specialist. In 2014, she was also honored with the International Institute for Peace Through Tourism’s Ambassador for Peace Award. Toni speaks six languages, holds a Doctorate in Educational Administration as well as a Masters in French Literature.