This January, the Indian State of Rajasthan passed an executive order barring anyone with less than eight years of formal education from running for election for head of village council (gram panchayat). This effectively disqualified roughly half of men and three-quarters of women from running in elections that began in January, and will impact more than 68 million of India’s people. Across the country, candidates in 170 elections ran unopposed. In at least seven gram panchayats, there were no willing candidates with the educational qualifications to run for office. Those posts remain vacant.

For International Women’s Day this March 8, we asked female leaders at one of our READ Centers in Baran, Rajasthan about how access to education impacts leadership opportunities within their communities.

The Jan Jagriti Gyan Kendra READ Center, which opened in 2010 in Bhawargarh village of the Baran district of Rajasthan, is entirely managed and operated by women.

Eleven of the thirteen women on the Center’s management committee have less than eight years of formal education, or none at all, making them ineligible to run for election under the new ordinance.

A majority of these women were pulled out of school at a young age due to social norms around the value of educating females. Only 48% of Rajasthani women are literate. It is common for rural families in India to end their daughter’s education early so the girls can work on the farm and in the home, or so they can be married off. If present trends continue, 130 million girls in South Asia will be married as children by 2030, ending their formal education and resulting in early pregnancies.

The Baran women agreed that basic literacy is important for elected leaders – male or female – so that they can read and sign documents, and access information on government programs.

Illiterate women are at risk of being taken advantage of in the political process. The Women’s Reservation Bill, passed in 2010 as part of a Constitutional amendment, placed a 33% quota for women in all seats in national and state legislatures. Yet oftentimes, when illiterate women are elected for panchayat head, they serve only nominally in place of their husbands. A husband can simply ask his illiterate wife for her thumbprint stamp of approval on an initiative, without her knowledge of what the document contains.

Because of the nuanced challenges to formal education and leadership in India, many women choose to pursue non-formal education, like the literacy, leadership, and livelihood skills trainings offered at READ Centers.

READ Centers in India provide literacy training as a first step that enables women to join community development activities, or other skills-based training programs. Centers also offer women’s empowerment trainings in leadership, civic participation, and confidence-building. Trainings in legal rights enable women to learn about their land ownership and voting rights, as well as government services for which they are eligible.

An independent evaluation of READ’s work in 2013 found that the non-formal education opportunities at READ Centers empowered women substantially:

- After getting involved with their local READ Center and its training programs, two thirds of women in India reported having more decision-making power in their families and communities on matters such as health care, their children’s education, spending, and family planning.

- 80% of women in India reported that their increased confidence and self-esteem enabled them to speak comfortably in public. Women reported joining committees, facilitating meetings, participating in protests, raising their voices against violence, and organizing community programs.

Indeed, many of the women committee leaders at the Baran READ Center became literate and gained leadership skills through the Center.

The women explained that while few people in their village have a complete formal education, most are very capable of understanding local issues, supporting community development, and serving as leaders.

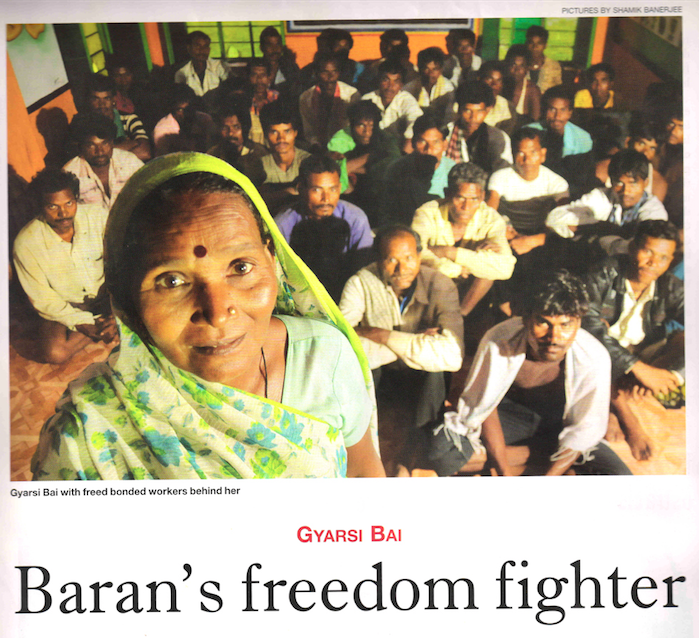

One of the many inspiring leaders at the Baran READ Center and in the larger community is a woman named Gyarsi Bai, an activist and community organizer.

Gyarsi Bai only made it through the fifth grade, but she has been working for more than a decade to fight for the land rights of the Sahariya, a historically landless tribe that was forced into bonded labor for generations.

Gyarsi Bai featured in the magazine Civil Society:

By building coalitions with larger activist groups and garnering media visibility, Gyarsi was able to reclaim land for her community. Gyarsi has also spurred local development in many other ways, from building a community grain bank to fight hunger, to creating savings cooperatives for women, to spreading awareness about the importance of girls’ education through the READ Center.

While Gyarsi clearly plays an invaluable role in her community, her lack of formal education means that she cannot run for election under the new ordinance.

The work of community members like Gyarsi proves that, in light of this new legislation, it’s more important now than ever to give women opportunities to gain an education and become leaders.

“For us, leadership means that an individual can fight for her own rights, is fully aware of her rights, can make independent decisions, and also respects other decisions or views,” says Meena Prajapat, one of the leaders of the Center.

“A leader is someone who gives other women the opportunity to move further. A true leader is a woman who is not afraid of sharing her views in front of others, who respects and helps other women and people in her community.”

READ Global has established four READ Centers in Rajasthan since 2010 – Geejgarh, Mamoni, Bhawargarh, and Devli – and all of them have management committees with a minimum of 33% representation by women. This co-gender leadership is essential to the long-term success and sustainability of Centers, which are owned and operated by local communities.

Share this blog post with your family and friends!

About the authors:

Sara Litke, READ Global Senior Program Officer

As READ Global’s Senior Program Officer, Sara manages the organization’s monitoring activities and oversees program evaluation efforts, as well as its marketing and communications strategy. She also supports institutional fundraising and grant writing, as well as new program initiatives and strategy for the global office. Sara also coordinates across all country offices to support the build out of sustaining enterprises. She joined the READ team in 2011 after two years of service as a Peace Corps volunteer in rural Mali, West Africa, where she worked with local villages in natural resource management and health.

Ms. Ruchika Dhingra, Program Coordinator, India

Ruchika has a Master’s in Social Work from Amity University. She has worked with several NGOs and CSR companies like HESCO, Salaam Baalak Trust, HCLT Foundation, and Public Policy Research Center as an intern. She joined the READ India team in 2014 as Project Coordinator and her responsibilities include documentation, reporting, collecting impact stories from READ Centers, and preparing monthly reports. She is also responsible for conducting life-skill trainings for women and children at all of the Centers.